Q+A with Bennett Sims about White Dialogues

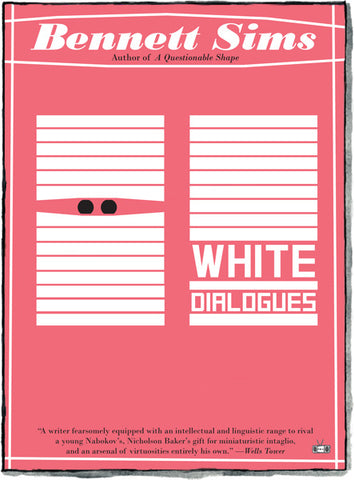

We are thrilled to share the news that we will be publishing a new book in September 2017 by Bennett Sims, award-winning author of A Questionable Shape. With all the brilliance, bravado, and wit of his debut, Bennett returns with an equally ambitious and wide-ranging collection of stories, titled White Dialogues.

A house-sitter alone in a cabin in the woods comes to suspect that the cabin may need to be “unghosted.” A raconteur watches as his life story is rewritten on an episode of This American Life. And in the collection’s title story, a Hitchcock scholar sitting in on a Vertigo lecture is gradually driven mad by his own theory of cinema.

These twelve stories shift from slow-burn psychological horror to playful comedy, bringing us into the minds of people who are haunted by their environments, obsessions, and doubts. Told in electric, insightful prose, White Dialogues is a profound exploration of the way we uncover meaning in a complex, and sometimes terrifying, world.

Following is an interview with Bennett about his new work.

Q: Generally, I find collections to be less ambitious as a whole than novels, but each of the stories here amazed me with its scope and calculation. They’re like novels, just shorter. What was the process of writing them like? Did you begin each story knowing it’d be a story?

Bennett: Thanks for the kind words. I did conceive of each story as a story, but I generally had to write a novel’s worth of material. The drafting documents for, say, ‘House-sitting’ run to hundreds of pages, and I worked on it for about two years, off and on. It was not a very efficient process. Part of my problem is that I typically begin a story knowing one major thing about it. For ‘House-sitting,’ I knew that I wanted to write a psychological horror story about a house-sitter going mad in a cabin in the woods. But I didn’t know a million very small, very basic things about it. Would it be in first person? Third? Would the cabin’s owner be present as a character? Would there be a pet to take care of in the cabin? Would the house-sitter have a backstory? Seemingly the only way I could dismiss an approach was through trial-and-error. I had to attempt it firsthand, and see it fail with my own eyes, before I could move on. So I wrote drafts from various points of view, wrote long passages about the house-sitter’s past, wrote scenes with the owner, or with the owner’s dog. And kept throwing the pages away.

Once I did determine the basic craft coordinates of the story (second person, present tense, no backstory), I still had to write the story itself, which involved writing multiple drafts of key scenes, drafting scenes I didn’t keep, experimenting with different narrative orders, and disposing of digressions, riffs, metaphors, etc. As I said, inefficient. It was the same with many of the other stories in the collection. So if some of them feel like compressed novels to you, I wonder whether it’s an artifact of this drafting process. Maybe there’s a kind of negative depth or density that a protractedly drafted story takes on, a way in which it conserves everything that’s ever been deleted inside it, like a black hole. In which case the hundreds of pages I had to write to get to the thirty pages would still be inside the thirty pages. It’s a consoling thought.

Q: A Questionable Shape was a book that took a subject matter generally regarded as lowbrow—zombies—and shifted the focus to highbrow discussion; the narrator’s references are similarly broad, ranging from Mad Max and the Goldeneye videogame to Kant and Euripides. Stories in White Dialogues, such as “Destroy All Monsters” and “Two Guys Watching Cujo On Mute,” seem to also enjoy a dip into genre (Kaiju films, ‘80s horror) before expanding into something much larger and unexpected. What’s your approach like?

Bennett: In general, I’m interested in the way that everyday consciousness is mediated by culture: how the way you see the world is inflected by the art you’ve seen, and how it doesn’t matter how high or low that art is. To phrase it a slightly different way—since the ‘high/low’ distinction is dubious—it doesn’t matter whether it’s art that you’re proud or ashamed to have seen, or that you even like all that much. I’ll take an example from life rather than from the book. Each fall I’m reliably reminded of Dragonball Z, an anime that I watched on Cartoon Network after school when I was a kid. In the show, martial artists can level up to ‘Super Saiyan’ status by clenching their fists and grimacing: when their inner energy or whatever is unleashed, their hair will burst into this flaming gold mane. So now every autumn, on that one morning when suddenly all the leaves on a maple have turned bright yellow overnight, I’ll find myself thinking, ‘The maple has gone Super Saiyan.’ To say that the tree reminds me of Dragonball Z is simply to say that my experience of it has been mediated by culture, by pop culture, by a cartoon. Because I happened to watch Dragonball Z at a formative age, its imagery is near the bottom of the phenomenological compost pile of my consciousness, where even now—years later—it continues to fertilize the way I see things. There is a pleasure, for me, in this association, and it runs parallel to whatever aesthetic pleasure I might derive from Dragonball Z. I don’t enjoy being reminded of that cartoon because it’s my favorite work of art (I think I was bored by it even at the time). Rather, I enjoy being reminded because analogy is inherently pleasurable.

This is a long answer to your question, but that tends to be the way I approach pop-culture and other artworks in fiction. They are part of the texture of the characters’ consciousness: they’re available to them as references or as raw material for the meaning-making, dot-connecting faculties of their minds. In A Questionable Shape, the characters are confronted with zombies in a world where zombie movies don’t exist, so they have to look toward other culture in order to interpret the creatures: Goldeneye, The Bacchae, Kant. In ‘Destroy All Monsters,’ a character is up late watching a gecko approach a moth on his windowpane, which reminds him, for obvious reasons, of Mothra vs. Godzilla. But he’s likewise reminded of Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones, King Lear, and the Old Testament story of Lot’s wife. His conscious experience of the windowpane is mediated by all of these other narratives, which is ultimately a characterizing detail (he has formative childhood memories of seeing Godzilla, etc.). And if he happens to have ‘larger’ questions on his mind (death, perception, epistemology), this is in part due to—not despite—having Godzilla on his mind (Godzilla films, after all, have traditionally also had larger questions on their minds).

Q: I’m an avid film fan, as I know you are, and I’m interested in the way films appear throughout your stories. How do you think about the influence of cinema on your work? For instance, a story like “White Dialogues” actually takes place at a lecture on Hitchcock’s Vertigo, a movie that it analyzes to the point of almost creating a new and unsettling filmic language. Whereas a story like “Housesitting” does not explicitly reference any movies but still reads cinematically to me: it’s extremely visual, like a slow-burn cerebral horror film (which I’d love to see get made one day).

Bennett: Thanks! For the most part, movies appear in my stories for the reasons I was discussing above, as a kind of referential reflex: because I frequently think about films, and because I like to write about thought, my characters end up thinking about films. It’s interesting that you highlighted ‘White Dialogues’ and ‘House-sitting,’ though. They’re both certainly influenced by cinema, but in different ways. In ‘White Dialogues,’ I wanted to write a kind of horror story about film theory. That is, I wanted to take seriously—to take literally—some of film theory’s more uncanny maxims: e.g., Andre Bazin’s proposition that films function like pyramids, preserving the bodies of the dead and thereby participating in mankind’s age-old ‘mummy complex’; or Roland Barthes’ observation that every photograph is haunted in advance by the death of its subject, since their present image is already irrigated by their future absence, which is why when looking at a photograph you are able to think the hauntological paradox ‘he is dead, and he is going to die’ (‘Whether or not the subject is already dead,’ Barthes writes, ‘every photograph is this catastrophe’). Finally, I wanted to take literally one of my favorite readings of a film, Jalal Toufic’s hypothesis in ‘Rear Window Vertigo’ that Rear Window and Vertigo are actually two halves of a single movie, in which James Stewart is playing split personalities of the same character. The title of the story, ‘White Dialogues,’ refers to a (as far as I know) made-up method of film analysis: hiring a lip-reader to analyze the extras in the background of a scene, to decode the silent conversations (the ‘white dialogues’) they’re having. This is something I’ve fantasized about doing since college, and for the story (or at least for its feverish narrator), I wanted lip-reading to be the thing that literalized all of these theories, confirming them. For what the extras in Vertigo appear to be saying is, basically, ‘We’re dead, leave us alone.’ White dialogues end up proving Barthes, Bazin, and Toufic right, in a way. And so one irony of the story is that this new method of reading produces no new knowledge for the narrator. When a film theorist reads extras’ lips, he just learns what deep down he already knew and has always feared: that actors really are ghosts and mummies; that a movie really is a haunted pyramid; that James Stewart’s character really did travel from Rear Window to Vertigo, in a kind of dissociative fugue.

‘House-sitting,’ on the other hand, was influenced by films more directly. I began it in part as an homage to Roman Polanski’s The Tenant, one of my favorite horror movies. In The Tenant, a man moves into the apartment of a woman who has attempted suicide: she leapt from the window into the courtyard below. While she slowly dies in a full-body cast in the hospital, her landlord lets the man take up residence in her apartment, which is still furnished with all of her belongings. Over the course of the film, the protagonist begins to suspect that he is the victim of a conspiracy: he becomes increasingly convinced that all of his neighbors in the apartment building are trying to turn him into the woman, projecting her identity onto him, so that he’ll jump out of the window too. By the end, he’s started wearing her dresses and putting on her makeup, and he does, in fact, leap from her window. It’s like a ghost movie without a ghost: the protagonist is possessed—not by the woman’s spirit—but by her possessions, by the fact that he has prematurely inhabited her space, which is still haunted by her habits. I wanted to write a horror story that was animated by a similar psychological dynamic, and I also wanted to write a cabin-in-the-woods story, in homage to one of my other favorite horror movies, Lars von Trier’s Antichrist. So ‘House-sitting’ began with that central conceit: a house-sitter moves to an abandoned cabin in the woods, only to become possessed by the previous tenant’s thought patterns.

What you called the story’s visual or cinematic style may be the result of these influences. But they’re also the likely byproduct of my writing process. My default mode of composition, when I don’t know what I’m doing or where I’m going, is description. For this story, I had that basic conceit (‘Protagonist moves to cabin, goes crazy’) but no real narrative strategy in mind. So my default process each day was to just keep describing the cabin, accreting details and hoping that a narrative pattern would emerge from them. Sitting down at my desk, I might spend a morning visualizing the backyard, the bathroom, the bedroom. I suppose it was a little as if I was ‘building a set’ for the story. I do remember that in a moment of impatience and despair at how long this was taking, I actually snatched a screen grab of the cabin from Antichrist and juxtaposed it with my Word document as I was writing. It was a kind of draughtsman’s exercise. I thought that if I simply copied down visual details from von Trier’s well-composed shot of a cabin—if I simply set the story inside von Trier’s cabin—the writing might go faster. But the photo was no help at all, and I abandoned the exercise after one morning. Reverting to my usual method, I kept describing random corners of the story (the tool shed out back; the dreamcatchers in the windows), until eventually I discovered what the story was: ‘Protagonist moves to cabin, goes crazy.’

You can pre-order White Dialogues now for 25% off.

If you are a bookseller, librarian, or critic interested in receiving an ARC of White Dialogues, you can do so here.

Comments