Q+A with Christine Lai about Landscapes

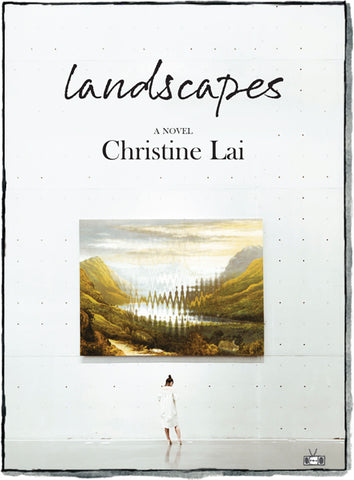

We're tremendously excited to share the news that on September 12, 2023, we will be publishing Landscapes, a debut novel by Christine Lai that brilliantly explores memory, empathy, preservation, and art as an instrument for recollection and renewal.

In the English countryside — decimated by heat and drought, earthquakes and floods — Penelope archives what remains of an estate’s once notable collection. As she catalogs the library’s contents, she keeps a diary of her final months in the dilapidated country house that has been her home for two decades and a refuge for those who have been displaced by disasters. Out of necessity, Penelope and her partner, Aidan, have sold the house and with its scheduled demolition comes this pressing task of completing the archive. But with it also comes the impending arrival of Aidan’s brother, Julian, who will return to have one final look at his childhood home. During a brief but violent relationship twenty-two years before, Penelope suffered at the hands of Julian, and as his visit looms, she finds herself unable to suppress the past in her efforts to build a possible, if uncertain, future.

This book? Wow. It calls to mind the work of Rachel Cusk, W.G. Sebald, and Kazuo Ishiguro, while heralding the arrival of a triumphant and spectacular new talent in Christine Lai.

What follows is an interview with Christine Lai about Landscapes.

QUESTION: Landscapes is such a brilliantly layered work. It’s mostly narrated by diary entries written by Penelope, but also features a more traditional narrative following Julian’s trek to Mornington Hall, and descriptions of archival items, with essays about artwork and culture that are interleaved between different sections. Many of the essays concern depictions of violence against women in art. What came first: the essays or the narrative, and did you always know the story needed to be told in such an epistolary manner?

CHRISTINE LAI: The diary as form came first. For a long time, I have been fascinated by the use of the epistolary within fiction, by diaristic works that seek to capture the rhythm and fragments of the everyday, that trace the contours of a life. A text I keep returning to is Rainer Maria Rilke’s novel, The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge. The “notebook” in the title comes from the German aufzeichnungen, for which “notebook” is not an exact translation. It also refers to jottings or sketches, and conveys a sense of disjointedness and incompletion. I wanted to write towards this idea of the incomplete, the fragmentary, which seemed to me a form suitable for capturing a consciousness. I love Jhumpa Lahiri’s remarks on diary-writing, in a recent Paris Review article:

“[Diaries and notebooks] are instances of self-doubling and self-fashioning. They are declarations of autonomy, counternarratives that contrast with and contradict reality.”

Of course, a novel is never really a diary, but in the style of a diary, so I was able to play with the passage of time, to narrate time as something slow and languorous at one point, then fast and intense at another. From Rilke I also learned to disrupt the reader’s expectations of a predictable, linear chronology, and of building a hybrid text, one in which narrative slides into essayism.

I’m equally drawn to the diaries of writers and artists. Kafka’s diaries were central to the development of Penelope’s entries. The sudden shifts in mood, the movement between daily observations and records of remembered dreams, the continual anxieties, the recounting of bodily sufferings—all these elements allude to Kafka. Although this is by no means a Kafkaesque novel, I was captivated by the image of Kafka sitting with his notebook, late into the night, constructing an interior world of his own. He considered his diary the only place where he could “hold on.” The diary becomes a sort of psychical and intellectual home, a “room of one’s own”—though home is always unstable.

I was also thinking of Louise Bourgeois’s diaries—she had three different diaries, one written, one verbal (recorded using a tape recorder), and one filled with drawings. She was driven by what she called a “tender compulsion” to keep these diaries. That phrase lingered in my mind for a long time. I did not want Penelope’s diary to be solely about a subjectivity in crisis. It is also about the texture of the quotidian, about readings and artworks, about catching "the pearls and coral” of life, to borrow the phrase Hannah Arendt used to describe Walter Benjamin’s note-taking. The archival items were introduced for this purpose. The archive structures Penelope’s days, and she frequently thinks through the objects, through their materiality and fragility. I found there was indeed an affinity between diary-writing and collecting, as Calvino expressed so eloquently in the essay “Collection of Sand,” a correspondence between the urge to write and the urge “to transform the flow of one’s existence into a series of objects.”

The inclusion of the objects turned parts of the book into a kind of catalogue, and from there, other forms emerged, including the essays on art, and the more traditional, linear third-person narrative. Over the years, I deposited numerous things into the book, serendipitously, haphazardly: readings, artworks, conversations, observations on the street. My composition method, if it could be called such, was modelled on Calvino’s, for the writing of Invisible Cities. In a lecture, he discussed how the fragments of the book, composed over the span of years, reflected his changing thoughts and experiences, so that “what emerged was a sort of diary which kept closely to [his] moods and reflections.” In many ways, a novel is its own kind of archive, and writing is a form of accumulation. The role of the writer is not unlike that of the archivist, bringing together images and ideas, saving them from dispersal and placing them into a collection that lends them meaning.

Q: It is a deeply visual novel, concerned with visual works of art that (usually) Penelope is describing in some way, as well as the sensation that these works evoke in the viewer. How do you see images and ideas intertwining within the book?

CL: The book is in many ways the result of an ongoing attempt to respond to the images that have arrested my attention at one point or another. For me, the process of writing always begins with looking at and thinking through images of artworks, of objects and buildings. Images are the springboards for ideas; or, rather, the process of attempting to unravel or comprehend the meaning of an image gives rise to narrative. Ek-phrasis is literally a “speaking out,” the work of giving voice to the silent object of art. All the devices that involve vision—the stereoscope, the Claude glass, the camera—were deliberately included to point to the centrality of the visual in Landscapes. I also collect literary works that incorporate ekphrastic encounters, everything ranging from Homer’s shield of Achilles to the scene in the Vatican in Middlemarch to Julian Barnes’s essay on Géricault in A History of the World in 10 ½ Chapters. I love tracing the way in which the artworks, or reflections on the artworks, refract a character’s experiences or interiority. I wanted to write in response to this long lineage of texts. But the visual does not always catalyze writing. It often challenges language, pushes it to its limit, so that sometimes there is only the silence. Penelope’s struggle with writing is very much my own.

I’m also interested in the ways in which images and the act of looking can be potentially obfuscating or limiting. This pertains to the artworks that depict sexual violence. To some art lovers, to even mention the subject is tantamount to a form of sacrilege, and perhaps people would much rather focus on an uncomplicated definition of beauty. I am indebted to feminist art historians who have compelled me to dismantle preconceived notions of beauty, to question my own sense of reverence towards the Old Masters. And I agree that we can interrogate the politics of these artworks while simultaneously acknowledging their vital contributions to art history. Perhaps more institutions could do what the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (home of Titian’s Rape of Europa) has done, and openly engage with the subject of power and sexual violence in artworks. I’m fascinated by the process by which we have collectively come to accept as beautiful something that is deeply problematic, even violent. We have overlooked beauty’s proximity to rot, to destruction. It leads to so many questions about the ethics of looking, about what it means to consume certain images.

Q: In addition to your method of delivery, I am curious about the story itself. When you boil it down, Landscapes is a story about a woman confronting the effects on her from a violent attack two decades before. How did you realize that was the story you wanted to pursue?

CL: The subject of sexual violence came after the reflections on art. When I began writing, I did not think about story, per se; I was more interested in form, in the image of a woman living in a dilapidated mansion, ruminating on art and archives. Turner’s Rape of Proserpine led me to consider the correspondence between architectural ruins (in the form of a crumbling castle in the painting) and the metaphoric ruination of a person. I wondered how someone who has been the target of an assault would encounter such a painting.

But I was more interested in the idea of reparation. For Penelope, writing constitutes the work of reparation. I remember reading, in the year prior to starting the novel, Annie Ernaux’s A Girl’s Story, in which she recounts the continual return to the past through the pages of the notebook, the drafting and redrafting of the account, and the meaning that emerges from that process. Kafka does something similar with his work. Writing-as-exorcism or writing-as-rebuilding also recalls the works of Louise Bourgeois, whose idea about art as a way of defeating the past was particularly resonant for me. In some ways, this book is also about art-making, about the art that emerges in the aftermath of an event. Penelope’s writing in the diary is akin to Bourgeois’s method of transmuting personal pain into art. Her openness is deliberately juxtaposed to the motifs of concealment and obfuscation that are associated with Julian.

I decided early on not to portray the actual scene of Penelope’s assault. It forms a kind of void at the center of the novel, echoed by the many images of voids or hollows that recur throughout the book—such as the Pompeii plaster casts, the hollow in a jewelry box, or the empty space on the gallery wall. The attempt to narrate violence was both an aesthetic and ethical challenge for me, and I wanted to explore whether suffering (especially someone else’s suffering) could be represented obliquely without commodifying or fetishizing pain. I was captivated by Doris Salcedo’s sculptures that speak of suffering without portraying the body in pain. The omissions or lacunae actually emphasize the violence, by tracing the outline around the moment of brutality or death. Sebald’s comments on the problem of representation were equally illuminating, his insistence that the “images [of horror] might militate against our capacity for discursive thinking . . . And also paralyze, as it were, our moral capacity” (The Emergence of Memory, p. 80). I hope the deliberate elision of the scene of violence is something that jumps out at the reader, so that the reader’s mind is drawn to that untold part of the story.

Q: Landscapes is made further unsettling by the setting. It takes place in a dystopian near-future, when floods and drought have ravaged the usually staid countryside in the United Kingdom. The environment is constantly present throughout the book, as Penelope contrasts the natural world—orchards, birds, and local wildlife—with how things were before. And then the estate that is to be torn down—Mornington Hall, owned by Aidan—where Penelope archives the library, is constantly crumbling, the setting mirroring Penelope’s progress in confronting her past. Meanwhile, Julian is traveling to Mornington Hall from Italy, shuttled by first-class carriages on trains, or in affluent bubbles that shelter neighborhoods from the environment, which also mirrors Julian’s character. The book has a dystopian setting, but I don’t believe it’s a dystopian novel. Were you ever concerned that folks would approach it as such?

CL: Over the course of the six years during which I wrote the novel, the news headlines have presented an inventory of catastrophes. What might have seemed unimaginable or faraway merely a few years ago—drought and flooding in Europe, extreme heat, the death of millions of marine animals—have become undeniable reality. In that sense, I do not see the book as dystopian. Reading the news compelled me to engage in eco-criticism, albeit in the space of a novel. That the story is set in a world that appears slightly different from the one the reader inhabits does not render it speculative, but rather, points to the very real possibility that such losses will only stack up over time, that catastrophe is past, present, and future. I wanted to elide the different periods of time in the narrative for that exact reason, so that they co-exist. I like Jenny Offill’s idea of “the pre-apocalyptic moment,” the moment in which we dwell, in which Penelope dwells. The instability, the decline, is already here. Climate change is already threatening the woodlands and heritage buildings in England. Destruction has been here all along. It is a matter of choosing to see its presence.

To me, it is ultimately a story about what it means to bear witness to catastrophe. In some ways, Penelope takes the stance of Benjamin’s angel of history, contemplating the wreckage of the past, attempting to preserve what is vanishing. There is no resolution here; that is beyond the scope of this novel. But I did want to attempt to think beyond disaster. The ruins of the house in which Penelope lives are regenerative in some sense—the place where she has rebuilt her life, and the site of the community she has created with Aidan and the others. Throughout the writing process, I collected representations or uses of ruins in artworks and literary texts. I was particularly interested in instances where the act of lingering in ruins becomes a way of working through both personal and collective crisis. In particular, I’m thinking of the film installation And yet my mask is powerful, by the Palestinian-American artists Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abu-Rahme, which showed individuals wandering through what remains of a Palestinian village and “rethinking the site of the wreckage.” I was also moved by Jenny Erpenbeck’s account, in Not a Novel, of playing amongst the rubble of East Berlin as a child. The dismantling then allows a place to become something new. Perhaps there is hope in that.

Q: Mornington Hall was passed down to Julian and then Aidan by their family. At its prominence, they accumulated an impressive library of artwork and artifacts that are kept in their collection rather than being made accessible to the public. On Julian’s travels across Europe, when he exits the safety of first class, he’s repulsed by crowded and uncomfortable trains, or by rowdy protests. How do you see this issue of class and access fitting into Landscapes?

CL: The issue of class certainly plays a role in Landscapes. Early in the research process, I was struck by John Berger’s seminal analysis, in Ways of Seeing, of Gainsborough’s Mr. and Mrs. Andrews, which portrays the landowners against the backdrop of their estate. The landscape is not merely something to be enjoyed visually, it is also property, just as the painted representation itself becomes another significant form of capital. This is something that is frequently forgotten or overlooked as we wander through museums and galleries: the price and ownership of everything.

Berger’s ideas on art-as-property and landscape-as-property pervade the novel (the title Landscapes is actually meant to be an homage to his works). I recall going through Sotheby’s website and coming across the page on Turner’s Ehrenbreitstein (sold in 2017 for over 18 million GBP), with a long list of successive collectors and grand houses in which the painting was once displayed. That image of the Turner at the heart of a collection gave rise to the country estate as the main setting, which reinforced the ideas about class and exclusivity. The idyllic English pastoral epitomized by the landscaped park is very much a construction, involving not only the enclosure of land and ancient ways, but also the displacement of peasants and the destruction of woodland. The formation of a country estate depended on the refusal of access in a very physical way. Sebald has already addressed this with great pathos in The Rings of Saturn, where the building of Ditchingham Hall necessitated the removal of anything unsightly, so that the owners of the house could enjoy “an uninterrupted view” in which “nothing offended the eye” (262). I return to Sebald’s work repeatedly, particularly to his descriptions of the dilapidated estates and the ecological devastation; many passages in Landscapes pay homage to his books.

The reference to colonial power is also important here. Many great houses were funded by wealth accrued through slavery and colonialism. There is an excellent essay in the New Yorker, by Sam Knight, that addresses the connection between slavery and the English stately home. The National Trust has also published a report that examines the colonial connections of 93 properties in their care. The beautiful house is therefore implicated in a history of destruction and exploitation. Yet we continue to visit these places, have tea there, stroll in the gardens. Much like how the violent subject of certain paintings is elided in discussions on the colours or mastery of technique, the history of the country estates is often forgotten in the face of beauty. Of course, Mornington Hall is ruinous, not a symbol of grandeur and elegance, and that ruination is important to me, necessary, even.

I don’t wish to be didactic or prescriptive about these issues. For one, Penelope was not born into privilege, and her relationship to art, to possessions, resists neat definitions. I simply wanted to explore, through the artworks and the house, how the act of looking is frequently entangled with the drive to take, to possess, so that looking is never an innocent act. And how this passion for ownership persists even when the desired object—whether that is a work of art, a person, a nation, or nature itself—never really belongs to us and always exceeds our grasp.

Q: What’s the road to publication been like for you?

CL: When I first began writing the book six years ago, I had no real expectations of being published. It was a solitary project that I undertook on weekends purely for my own sake. I was driven by my own sense of “tender compulsion.” Making the jump from academic writing to creative work was a daunting process, but I really appreciate the capaciousness of fiction, the ambiguities that it allows.

I never really had a writing community, so I did not discuss the book in detail with anyone, though my peers at the Writers Studio at Simon Fraser University read an early version of Ch. 1, and my mentors at the Banff Center gave invaluable feedback for the first two chapters. Being shortlisted for the Novel Prize—offered by New Directions, Fitzcarraldo Editions, and Giramondo—was really the first indication that there might be the possibility, however remote, that the book would find an audience. I was incredibly honored to be shortlisted alongside such brilliant writers, and it galvanized me to revise the manuscript rigorously before submitting to agents. The waiting was perhaps the most stressful part—the waiting for response, for feedback. But I’m fortunate to have found an agent and editors who believe in the project. I’m frankly still astounded that any of this happened at all. The feeling of gratitude, and perhaps disbelief, has been a major part of my experience with publishing.

At present, I am slightly terrified by the thought that something as private as the book will be sent out into the world, to be read by others. It might take me a while to get used to the idea of the book as an object, belonging to the reader, something that is no longer my own archive of “pearls and coral.”

Booksellers, librarians, or critics interested in receiving an advance copy of Landscapes can request a copy.

Pre-order Landscapes.

Comments