I’m visiting from New York City, where, since December, the public libraries have been closed on Sundays, owing to budget cuts by the mayor, who is a villain right out of a Marvel comic.

| Read more →⭐ We have a different website for our Ohio bookstore + cafe! Visit it here. ⭐

I’m visiting from New York City, where, since December, the public libraries have been closed on Sundays, owing to budget cuts by the mayor, who is a villain right out of a Marvel comic.

| Read more →

On January 23, 2024, we're thrilled to release Zachary Pace's debut book, I Sing to Use the Waiting: A Collection of Essays About the Women Singers Who've Made Me Who I Am. With remarkable grace, candor, and a poet’s ear for prose, Zachary Pace recounts the women singers — from Cat Power to Madonna, Kim Gordon to Rihanna — who shaped them as a young person coming-of-age in rural New York, first discovering their own queer voice.

Structured like a mixtape, Pace juxtaposes their coming out with the music that informed them along the way. They recount how listening to themselves sing along as a child to a Disney theme song they recorded on a boom box in 1995, was when they first realized there was an effeminate inflection to their voice. As childhood friendships splinter, Pace discusses the relationship between Whitney Houston and Robyn Crawford. Cat Power’s song “My Daddy Was a Musician” spurs a discussion of Pace’s own musician father, and their gradual estrangement.

Resonant and compelling, I Sing to Use the Waiting is a deeply personal rumination on how queer stories are abundant yet often suppressed, and how music may act as a comforting balm carrying us through difficult periods and decisions.

Eileen Myles says: "Zachary Pace takes listening & fanhood to a teeming level of worship which is exactly what it is. Beautiful precise quirky bodily cerebral listening to female vocalists and writing about it. I’m so in awe of what I get when I read this dedicated performance of that. I think Kim (Gordon) should hear, Chan (Marshall) should hear. The chapter on the Kabbalah (and Madonna) was so astonishing. God should hear too: this miraculous and fun and deeply cool book that’s really about sound and our relationship to it, gendered, historic, mortal and true."

Wayne Koestenbaum says: "I’ve been waiting a long time to read a book as soulful and precise, in its treatment of listening, as Zachary Pace’s tender account of an identity put back together through the powerful elixir of singing women. Pace, a lover of the overlooked, attends to the brocaded minutiae of triumphs, comebacks, travails. To enunciation and excess, Pace brings a curatively lucid eye and ear, each vignette invested with lyric care, and with a fastidious affection for the contours of a singer’s career. This impeccable book sends me back, with a renewed heart, to the songs Pace masterfully covers, with a delivery as splendid, as emotionally impressive, as the lauded originals."

Following is an interview with Pace about the book.

Question: You are originally a poet, how did a collection of personal essays about music and musicians come about?

Zachary Pace: In 2016, when the forty-fifth US president was elected, I felt the need to make writing that would preserve certain values that were suddenly even more imperiled than they had been: queerness, femininity, what the amazing Jessica Hopper calls “matrilineage”—history that centers the influence and power of women and femme people—subjects that we’re so fortunate to have the space to write about here and now, because we haven’t always been able to, and we may not always be able to, which became increasingly clear to me in 2016.

But I couldn’t say what I needed to say in poems. I have a kind of cramped and overly precious relationship to the information that I can put into and get out of writing poetry. In one of the only recordings of Sylvia Plath’s voice, in an interview, she says that she could never use the word “toothbrush[ZP1]” in a poem. I have a similar difficulty in letting the toothbrushes of the world into my poetry. But now I want to make writing that has room for all the stuff of life, and in the personal essay, I found room for the toothbrush.

My favorite musician is the great Chan Marshall, who performs and records as Cat Power, and I spent a lot of time listening to bootlegs from all stages of her long and ongoing career. When I stopped feeling the need to make poems, I started noticing a narrative running through the bootlegs and wanted to try to tell the story. Greil Marcus’s book about Bob Dylan’s bootlegs, Like a Rolling Stone, inspired me to look through the microscope of one song. My partner at the time, the wise and gifted writer Eric Dean Wilson, found a copy of Hanif Abdurraqib’s They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us (which had just come out) and gave it to me, saying, “I think this will be your jam.” That book inspired me to keep going, and so it’s unbelievably meaningful that Two Dollar Radio became the home for my book.

Q: How do you feel music has informed your identity?

ZP: I’ve used music to self-soothe since I was a kid. I remember, when I was three or four, putting a 45 on the record player at preschool—the A-side was “Bella Notte” from Disney’s The Lady and the Tramp—and listening so many times, it got too scuffed to play. When I was four or five, my anthem was “Heaven Is a Place on Earth” by Belinda Carlisle, and I’d stare at her glamour shot on the Heaven on Earth cassette’s insert, wishing so badly to look like that. I cultivated my personality through mimicking the gestures of singers. And their music has been my constant companion. It has given me language to articulate emotions that I couldn’t express on my own. It makes me feel more legible.

Q: The essays all deal with your personal development alongside music and artists, whether that be through the tattoos you have that came about through a stint with the Kabbalah (via Madonna), or the sense of invincibility you feel in teenage years and how that translates through the music of Kim Gordon. Did setting parameters—personally, musically—help spark the creative direction of the book and its subjects rather than feeling restrictive?

ZP: The only parameter I set was to listen to the music that I was writing about as frequently as possible. Especially with Cat Power, Kim Gordon, Rihanna, Whitney Houston, and Frances Quinlan—when writing those essays, I made a rule: I had to listen to their music exclusively. I could listen to someone else for a palate cleanser on rare occasion, but honestly, I listened only to the musician I was writing about at the time.

Aside from that, I had no rules, and the process was totally liberating. Not only did I find room for the proverbial toothbrush, I found the space to tell stories that I’ve always wanted to share—and stumbled on some stories I didn’t know were waiting there. My personal narrative is present in all but two essays: the one on Cher and the one on Rihanna. For the Cher essay, I couldn’t find a way to narrate my experience alongside hers, but the two films at the center—Mask and Mermaids—were hugely influential to me when I was growing up. The Rihanna essay centers around the effects of colonialism on the history of music in Barbados, which was important to me not to narrate through my “I.” For the Madonna essay, my personal narrative came first; this is the story I wish I could tell whenever I’m asked what my tattoos mean. The Kim Gordon essay started with the music—I set out to tell the story of the final song on the final Sonic Youth record—and my personal narrative was secondary to Kim’s.

Formally, the main and maybe only difference between how I make a poem and an essay is the use of line endings, which play a big part in the logic of my poems. Writing without line endings liberated the way I make sentences. But when I’m making an essay, I’m using all the other tools I’d use to make poetry, including poem-logic: I try to prove the thesis both through factual evidence and through poetic tools like repetition, litany, alliteration and assonance, even rhyme.

Q: One of my favorite essays in the collection is “Ballad of Robyn and Whitney,” in which you focus on Whitney Houston’s relationship with Robyn Crawford, and the social, familial, and business forces that pried them apart. It’s less about the actual music, and more about the “heterosexist requirements of pop culture.” How do you see Robyn and Whitney’s relationship relating to your own personal evolution?

ZP: I learned a lot later in life. When I was a kid, The Bodyguard, Waiting to Exhale, and The Preacher’s Wife films and soundtracks were on constant rotation. I was magnetized by Whitney’s star quality. Between 2017 and 2018, two documentaries on Whitney were released, and both spoke to her relationship with Robyn Crawford. I’d never heard of Robyn, and the reason I’d never heard of Robyn is because the industry and the family did everything that they could to conceal the relationship. The relationship was queer, and it was vital to Whitney’s well-being.

Robyn published a memoir in 2019, while I was still deep in writing the essay, and all the information coalesced around then. Sarah Schulman’s crucial book Ties That Bind gave me the language—“familial homophobia”—to tell the story, along with the attachment theory of John Bowlby, who believed that an infant’s first separation from the mother figure sets the tone for the individual’s attachment and separation styles later in life.

My personal narrative bookends the essay because, at some point, I realized that one of my earliest attachment-separations was the result of homophobia—and that it occurred during the years I was most obsessed with Whitney. Telling that story here is cathartic, and it may help me along in the grieving process.

I don’t necessarily believe in ghosts, but I do believe I had two visitations from Whitney while I was writing the essay.

Q: The last essay in the collection concerns the song “The Color of the Wind,” from the Disney movie, Pocahontas. You recount how when you were ten years old, you would record yourself singing along to the song, and it was the first time that you recognized your voice as containing inflections you flag as queer. How do you believe voice relates to identity?

ZP: I believe it is paramount. And I believe this is true even for people who can’t speak; if a person can’t speak, the absence of voice is perceived by the dominant society through certain frameworks—primarily those of ability and disability. A lot of assumptions and judgments are made by the dominant society based on how a person fits or doesn’t fit within these frameworks, or standards of normativity, which are bound to inform a person’s self-perception and thus structure their identity.

If a person can speak, their voice is perceived through other standards of normativity—primarily those of gender. Since the dominant society is largely homophobic and transphobic, the more your voice matches your gender presentation, the better your legibility. People modulate their voices to become more legible all the time. You can hear, in a voice, when a person is sure of themselves. And you can hear it when they aren’t.

I believe the voice is one of the top three factors (along with face and name) by which a speaking person becomes recognized and known by others.

Q: You cover female musicians from a broad swath of genres, from Rihanna to Whitney Houston to Cat Power. Were there any musicians you feel were formative to your development that you ended up leaving out of the collection?

ZP: Countless. Sheryl Crow, for one: I’ve been looking for but can’t find a photograph of her that I loved when I was a kid—I used to mimic her facial expression in the photo, and it remains one of my default facial expressions to this day. Bonnie Raitt. Tracy Chapman. Jenny Lewis. Sade. Alanis Morissette, Shania Twain, Sarah McLachlan, Céline Dion. Selena. Regina Spektor. Natalie Merchant. Trisha Yearwood. An album called “Comatised” by Leona Naess was the soundtrack to my first big crush, and it takes me back in one note. The list goes on. I just couldn’t find a strong enough story to tell there, but maybe one day I will. I’m working on what I hope will be a book about Alice Coltrane, whose discography includes one album that features her voice: Turiya Sings.

[ZP1]Skip to 10:22 and listen through 11:20 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g2lMsVpRh5c

Booksellers, librarians, and critics interested in receiving an advance reading copy of I Sing to Use the Waiting may request one here.

Pre-order your own copy of I Sing to Use the Waiting.

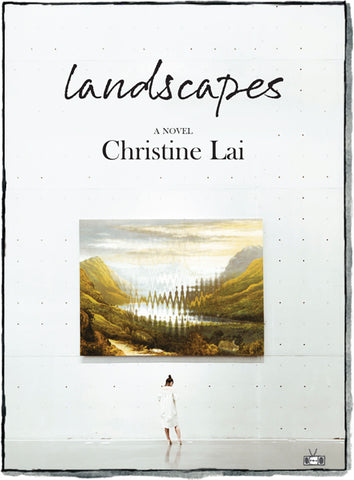

We're tremendously excited to share the news that on September 12, 2023, we will be publishing Landscapes, a debut novel by Christine Lai that brilliantly explores memory, empathy, preservation, and art as an instrument for recollection and renewal.

In the English countryside — decimated by heat and drought, earthquakes and floods — Penelope archives what remains of an estate’s once notable collection. As she catalogs the library’s contents, she keeps a diary of her final months in the dilapidated country house that has been her home for two decades and a refuge for those who have been displaced by disasters. Out of necessity, Penelope and her partner, Aidan, have sold the house and with its scheduled demolition comes this pressing task of completing the archive. But with it also comes the impending arrival of Aidan’s brother, Julian, who will return to have one final look at his childhood home. During a brief but violent relationship twenty-two years before, Penelope suffered at the hands of Julian, and as his visit looms, she finds herself unable to suppress the past in her efforts to build a possible, if uncertain, future.

This book? Wow. It calls to mind the work of Rachel Cusk, W.G. Sebald, and Kazuo Ishiguro, while heralding the arrival of a triumphant and spectacular new talent in Christine Lai.

What follows is an interview with Christine Lai about Landscapes.

QUESTION: Landscapes is such a brilliantly layered work. It’s mostly narrated by diary entries written by Penelope, but also features a more traditional narrative following Julian’s trek to Mornington Hall, and descriptions of archival items, with essays about artwork and culture that are interleaved between different sections. Many of the essays concern depictions of violence against women in art. What came first: the essays or the narrative, and did you always know the story needed to be told in such an epistolary manner?

CHRISTINE LAI: The diary as form came first. For a long time, I have been fascinated by the use of the epistolary within fiction, by diaristic works that seek to capture the rhythm and fragments of the everyday, that trace the contours of a life. A text I keep returning to is Rainer Maria Rilke’s novel, The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge. The “notebook” in the title comes from the German aufzeichnungen, for which “notebook” is not an exact translation. It also refers to jottings or sketches, and conveys a sense of disjointedness and incompletion. I wanted to write towards this idea of the incomplete, the fragmentary, which seemed to me a form suitable for capturing a consciousness. I love Jhumpa Lahiri’s remarks on diary-writing, in a recent Paris Review article:

“[Diaries and notebooks] are instances of self-doubling and self-fashioning. They are declarations of autonomy, counternarratives that contrast with and contradict reality.”

Of course, a novel is never really a diary, but in the style of a diary, so I was able to play with the passage of time, to narrate time as something slow and languorous at one point, then fast and intense at another. From Rilke I also learned to disrupt the reader’s expectations of a predictable, linear chronology, and of building a hybrid text, one in which narrative slides into essayism.

I’m equally drawn to the diaries of writers and artists. Kafka’s diaries were central to the development of Penelope’s entries. The sudden shifts in mood, the movement between daily observations and records of remembered dreams, the continual anxieties, the recounting of bodily sufferings—all these elements allude to Kafka. Although this is by no means a Kafkaesque novel, I was captivated by the image of Kafka sitting with his notebook, late into the night, constructing an interior world of his own. He considered his diary the only place where he could “hold on.” The diary becomes a sort of psychical and intellectual home, a “room of one’s own”—though home is always unstable.

I was also thinking of Louise Bourgeois’s diaries—she had three different diaries, one written, one verbal (recorded using a tape recorder), and one filled with drawings. She was driven by what she called a “tender compulsion” to keep these diaries. That phrase lingered in my mind for a long time. I did not want Penelope’s diary to be solely about a subjectivity in crisis. It is also about the texture of the quotidian, about readings and artworks, about catching "the pearls and coral” of life, to borrow the phrase Hannah Arendt used to describe Walter Benjamin’s note-taking. The archival items were introduced for this purpose. The archive structures Penelope’s days, and she frequently thinks through the objects, through their materiality and fragility. I found there was indeed an affinity between diary-writing and collecting, as Calvino expressed so eloquently in the essay “Collection of Sand,” a correspondence between the urge to write and the urge “to transform the flow of one’s existence into a series of objects.”

The inclusion of the objects turned parts of the book into a kind of catalogue, and from there, other forms emerged, including the essays on art, and the more traditional, linear third-person narrative. Over the years, I deposited numerous things into the book, serendipitously, haphazardly: readings, artworks, conversations, observations on the street. My composition method, if it could be called such, was modelled on Calvino’s, for the writing of Invisible Cities. In a lecture, he discussed how the fragments of the book, composed over the span of years, reflected his changing thoughts and experiences, so that “what emerged was a sort of diary which kept closely to [his] moods and reflections.” In many ways, a novel is its own kind of archive, and writing is a form of accumulation. The role of the writer is not unlike that of the archivist, bringing together images and ideas, saving them from dispersal and placing them into a collection that lends them meaning.

Q: It is a deeply visual novel, concerned with visual works of art that (usually) Penelope is describing in some way, as well as the sensation that these works evoke in the viewer. How do you see images and ideas intertwining within the book?

CL: The book is in many ways the result of an ongoing attempt to respond to the images that have arrested my attention at one point or another. For me, the process of writing always begins with looking at and thinking through images of artworks, of objects and buildings. Images are the springboards for ideas; or, rather, the process of attempting to unravel or comprehend the meaning of an image gives rise to narrative. Ek-phrasis is literally a “speaking out,” the work of giving voice to the silent object of art. All the devices that involve vision—the stereoscope, the Claude glass, the camera—were deliberately included to point to the centrality of the visual in Landscapes. I also collect literary works that incorporate ekphrastic encounters, everything ranging from Homer’s shield of Achilles to the scene in the Vatican in Middlemarch to Julian Barnes’s essay on Géricault in A History of the World in 10 ½ Chapters. I love tracing the way in which the artworks, or reflections on the artworks, refract a character’s experiences or interiority. I wanted to write in response to this long lineage of texts. But the visual does not always catalyze writing. It often challenges language, pushes it to its limit, so that sometimes there is only the silence. Penelope’s struggle with writing is very much my own.

I’m also interested in the ways in which images and the act of looking can be potentially obfuscating or limiting. This pertains to the artworks that depict sexual violence. To some art lovers, to even mention the subject is tantamount to a form of sacrilege, and perhaps people would much rather focus on an uncomplicated definition of beauty. I am indebted to feminist art historians who have compelled me to dismantle preconceived notions of beauty, to question my own sense of reverence towards the Old Masters. And I agree that we can interrogate the politics of these artworks while simultaneously acknowledging their vital contributions to art history. Perhaps more institutions could do what the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (home of Titian’s Rape of Europa) has done, and openly engage with the subject of power and sexual violence in artworks. I’m fascinated by the process by which we have collectively come to accept as beautiful something that is deeply problematic, even violent. We have overlooked beauty’s proximity to rot, to destruction. It leads to so many questions about the ethics of looking, about what it means to consume certain images.

Q: In addition to your method of delivery, I am curious about the story itself. When you boil it down, Landscapes is a story about a woman confronting the effects on her from a violent attack two decades before. How did you realize that was the story you wanted to pursue?

CL: The subject of sexual violence came after the reflections on art. When I began writing, I did not think about story, per se; I was more interested in form, in the image of a woman living in a dilapidated mansion, ruminating on art and archives. Turner’s Rape of Proserpine led me to consider the correspondence between architectural ruins (in the form of a crumbling castle in the painting) and the metaphoric ruination of a person. I wondered how someone who has been the target of an assault would encounter such a painting.

But I was more interested in the idea of reparation. For Penelope, writing constitutes the work of reparation. I remember reading, in the year prior to starting the novel, Annie Ernaux’s A Girl’s Story, in which she recounts the continual return to the past through the pages of the notebook, the drafting and redrafting of the account, and the meaning that emerges from that process. Kafka does something similar with his work. Writing-as-exorcism or writing-as-rebuilding also recalls the works of Louise Bourgeois, whose idea about art as a way of defeating the past was particularly resonant for me. In some ways, this book is also about art-making, about the art that emerges in the aftermath of an event. Penelope’s writing in the diary is akin to Bourgeois’s method of transmuting personal pain into art. Her openness is deliberately juxtaposed to the motifs of concealment and obfuscation that are associated with Julian.

I decided early on not to portray the actual scene of Penelope’s assault. It forms a kind of void at the center of the novel, echoed by the many images of voids or hollows that recur throughout the book—such as the Pompeii plaster casts, the hollow in a jewelry box, or the empty space on the gallery wall. The attempt to narrate violence was both an aesthetic and ethical challenge for me, and I wanted to explore whether suffering (especially someone else’s suffering) could be represented obliquely without commodifying or fetishizing pain. I was captivated by Doris Salcedo’s sculptures that speak of suffering without portraying the body in pain. The omissions or lacunae actually emphasize the violence, by tracing the outline around the moment of brutality or death. Sebald’s comments on the problem of representation were equally illuminating, his insistence that the “images [of horror] might militate against our capacity for discursive thinking . . . And also paralyze, as it were, our moral capacity” (The Emergence of Memory, p. 80). I hope the deliberate elision of the scene of violence is something that jumps out at the reader, so that the reader’s mind is drawn to that untold part of the story.

Q: Landscapes is made further unsettling by the setting. It takes place in a dystopian near-future, when floods and drought have ravaged the usually staid countryside in the United Kingdom. The environment is constantly present throughout the book, as Penelope contrasts the natural world—orchards, birds, and local wildlife—with how things were before. And then the estate that is to be torn down—Mornington Hall, owned by Aidan—where Penelope archives the library, is constantly crumbling, the setting mirroring Penelope’s progress in confronting her past. Meanwhile, Julian is traveling to Mornington Hall from Italy, shuttled by first-class carriages on trains, or in affluent bubbles that shelter neighborhoods from the environment, which also mirrors Julian’s character. The book has a dystopian setting, but I don’t believe it’s a dystopian novel. Were you ever concerned that folks would approach it as such?

CL: Over the course of the six years during which I wrote the novel, the news headlines have presented an inventory of catastrophes. What might have seemed unimaginable or faraway merely a few years ago—drought and flooding in Europe, extreme heat, the death of millions of marine animals—have become undeniable reality. In that sense, I do not see the book as dystopian. Reading the news compelled me to engage in eco-criticism, albeit in the space of a novel. That the story is set in a world that appears slightly different from the one the reader inhabits does not render it speculative, but rather, points to the very real possibility that such losses will only stack up over time, that catastrophe is past, present, and future. I wanted to elide the different periods of time in the narrative for that exact reason, so that they co-exist. I like Jenny Offill’s idea of “the pre-apocalyptic moment,” the moment in which we dwell, in which Penelope dwells. The instability, the decline, is already here. Climate change is already threatening the woodlands and heritage buildings in England. Destruction has been here all along. It is a matter of choosing to see its presence.

To me, it is ultimately a story about what it means to bear witness to catastrophe. In some ways, Penelope takes the stance of Benjamin’s angel of history, contemplating the wreckage of the past, attempting to preserve what is vanishing. There is no resolution here; that is beyond the scope of this novel. But I did want to attempt to think beyond disaster. The ruins of the house in which Penelope lives are regenerative in some sense—the place where she has rebuilt her life, and the site of the community she has created with Aidan and the others. Throughout the writing process, I collected representations or uses of ruins in artworks and literary texts. I was particularly interested in instances where the act of lingering in ruins becomes a way of working through both personal and collective crisis. In particular, I’m thinking of the film installation And yet my mask is powerful, by the Palestinian-American artists Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abu-Rahme, which showed individuals wandering through what remains of a Palestinian village and “rethinking the site of the wreckage.” I was also moved by Jenny Erpenbeck’s account, in Not a Novel, of playing amongst the rubble of East Berlin as a child. The dismantling then allows a place to become something new. Perhaps there is hope in that.

Q: Mornington Hall was passed down to Julian and then Aidan by their family. At its prominence, they accumulated an impressive library of artwork and artifacts that are kept in their collection rather than being made accessible to the public. On Julian’s travels across Europe, when he exits the safety of first class, he’s repulsed by crowded and uncomfortable trains, or by rowdy protests. How do you see this issue of class and access fitting into Landscapes?

CL: The issue of class certainly plays a role in Landscapes. Early in the research process, I was struck by John Berger’s seminal analysis, in Ways of Seeing, of Gainsborough’s Mr. and Mrs. Andrews, which portrays the landowners against the backdrop of their estate. The landscape is not merely something to be enjoyed visually, it is also property, just as the painted representation itself becomes another significant form of capital. This is something that is frequently forgotten or overlooked as we wander through museums and galleries: the price and ownership of everything.

Berger’s ideas on art-as-property and landscape-as-property pervade the novel (the title Landscapes is actually meant to be an homage to his works). I recall going through Sotheby’s website and coming across the page on Turner’s Ehrenbreitstein (sold in 2017 for over 18 million GBP), with a long list of successive collectors and grand houses in which the painting was once displayed. That image of the Turner at the heart of a collection gave rise to the country estate as the main setting, which reinforced the ideas about class and exclusivity. The idyllic English pastoral epitomized by the landscaped park is very much a construction, involving not only the enclosure of land and ancient ways, but also the displacement of peasants and the destruction of woodland. The formation of a country estate depended on the refusal of access in a very physical way. Sebald has already addressed this with great pathos in The Rings of Saturn, where the building of Ditchingham Hall necessitated the removal of anything unsightly, so that the owners of the house could enjoy “an uninterrupted view” in which “nothing offended the eye” (262). I return to Sebald’s work repeatedly, particularly to his descriptions of the dilapidated estates and the ecological devastation; many passages in Landscapes pay homage to his books.

The reference to colonial power is also important here. Many great houses were funded by wealth accrued through slavery and colonialism. There is an excellent essay in the New Yorker, by Sam Knight, that addresses the connection between slavery and the English stately home. The National Trust has also published a report that examines the colonial connections of 93 properties in their care. The beautiful house is therefore implicated in a history of destruction and exploitation. Yet we continue to visit these places, have tea there, stroll in the gardens. Much like how the violent subject of certain paintings is elided in discussions on the colours or mastery of technique, the history of the country estates is often forgotten in the face of beauty. Of course, Mornington Hall is ruinous, not a symbol of grandeur and elegance, and that ruination is important to me, necessary, even.

I don’t wish to be didactic or prescriptive about these issues. For one, Penelope was not born into privilege, and her relationship to art, to possessions, resists neat definitions. I simply wanted to explore, through the artworks and the house, how the act of looking is frequently entangled with the drive to take, to possess, so that looking is never an innocent act. And how this passion for ownership persists even when the desired object—whether that is a work of art, a person, a nation, or nature itself—never really belongs to us and always exceeds our grasp.

Q: What’s the road to publication been like for you?

CL: When I first began writing the book six years ago, I had no real expectations of being published. It was a solitary project that I undertook on weekends purely for my own sake. I was driven by my own sense of “tender compulsion.” Making the jump from academic writing to creative work was a daunting process, but I really appreciate the capaciousness of fiction, the ambiguities that it allows.

I never really had a writing community, so I did not discuss the book in detail with anyone, though my peers at the Writers Studio at Simon Fraser University read an early version of Ch. 1, and my mentors at the Banff Center gave invaluable feedback for the first two chapters. Being shortlisted for the Novel Prize—offered by New Directions, Fitzcarraldo Editions, and Giramondo—was really the first indication that there might be the possibility, however remote, that the book would find an audience. I was incredibly honored to be shortlisted alongside such brilliant writers, and it galvanized me to revise the manuscript rigorously before submitting to agents. The waiting was perhaps the most stressful part—the waiting for response, for feedback. But I’m fortunate to have found an agent and editors who believe in the project. I’m frankly still astounded that any of this happened at all. The feeling of gratitude, and perhaps disbelief, has been a major part of my experience with publishing.

At present, I am slightly terrified by the thought that something as private as the book will be sent out into the world, to be read by others. It might take me a while to get used to the idea of the book as an object, belonging to the reader, something that is no longer my own archive of “pearls and coral.”

Booksellers, librarians, or critics interested in receiving an advance copy of Landscapes can request a copy.

Pre-order Landscapes.

Bennett Sims' writing has won the Rome Prize for Literature and the Bard Fiction Prize. For Bookforum, Tony Tulathimutte called Sims “possibly the smartest and most inventive writer of his... generation,” while for LitHub Carmen Maria Machado says Sims is “kind of like if Alfred Hitchcock and Brian Evenson raised a baby with David Foster Wallace and Nicholson Baker.” Writing for the New York Times Book Review, Hannah Pittard compared Sims to Poe and praised his “pyrotechnics of language.”

We published Bennett's debut novel, A Questionable Shape, in 2013. The book is one of my favorite to hand-sell, in that it's a meditation on father-son relationships under the guise of a zombie novel, but with barely any actual zombies in it. His story collection, White Dialogues, which we published in 2017, is like a Hitchcock film narrated by Ira Glass, with ratcheting tension and dread.

In November 2023, we're incredibly thrilled and honored to be publishing Bennett's brilliant, anxious, and hilarious new story collection, Other Minds and Other Stories. A man lends his phone to a stranger in the mall, setting off an uncanny series of Unknown calls that come to haunt his relationship with jealousy and dread. A well-meaning locavore tries to butcher his backyard chickens humanely, only to find himself absorbed into the absurd violence of the pecking order. A student applying for a philosophy fellowship struggles to project himself into the thoughts of his hypothetical judges, becoming increasingly possessed and overpowered by the problem of other minds. And in “The Postcard,” a private detective is hired to investigate a posthumous message that a widower has seemingly received from his dead wife, leading him into a foggy landscape of lost memories, shifting identities, and strange doublings.

The long and short of it is, I could never have predicted that I’d laugh so hard at a story about a man euthanizing his backyard chicken flock. I never imagined I’d be so unnerved at a story about something as mundane as picking up a new cellphone from a mall outlet store. I would insist that there is no realistic way that you could boil down the transcendent sway of literature to a story that lasts a single page. But Bennett did that, in stories in this new collection, cause he’s a magician.

Following is an interview with Bennett about Other Minds and Other Stories.

Q: Your writing seeks to explore the labyrinthine processes of human thought and the anxiety that might go along with that. Writers are supposed to occupy their characters’ minds, but you go much farther to dig through the minutiae of the process. What fascinates you as a writer about exploring other minds?

Bennett Sims: There’s a line that appears in a couple of the stories, and serves as a refrain throughout the collection: ‘All his life, if someone had asked him why he read, the reader would have answered that he was curious about other minds.’ This is, unironically, why I read. Literature preserves the conscious experience of other minds in language. Reading the work is the only way I’ll know, however approximately, what it was like for them: the different, the distant, the dead.

The characters in this collection are all also, in their own ways, curious about other minds. But as you point out, it’s an anxious curiosity. Their attempts to fathom what other people might be thinking—to model ‘what it is like’ for them—often frighten them. A jealous lover becomes suspicious of his partner: who is she texting each night? A man forced to behead a chicken can’t help projecting himself inside the dying chicken’s mind. In the title story, someone reading an ebook is baffled by the lines that other readers have highlighted, and becomes gripped by the epistemological vertigo intrinsic to all aesthetic judgment: why did they highlight those lines? What was going on inside their heads as they read?

Part of what fascinates me about exploring other minds, then, are the ways that they explore other minds. How does one character struggle to understand another, or construct another’s subjectivity? This exercise in empathy isn’t always benign, after all. Stylistically, I enjoy pursuing characters’ curiosity about each other until the sentences begin to spiral out into darker directions: paranoia, obsession, dread.

I borrowed the title ‘Other Minds’ from works of philosophy and ethology that are engaged with the Nagelian question of nonhuman consciousness: what is it like to be a bat, or an octopus, or even, say, an object (a rock, an electron, etc.)? The characters in this collection frequently attempt to project themselves into nonhuman subjectivities as well: chickens, wind, snow, ghosts. This is also true of my other books, where characters come to be curious about chipmunks, zombies, mites, ice cubes. The pleasure of the writing remains the same, for me. I enjoy tracking the movements of their minds as they send out their little empathy tendrils, deep into the territory of some other what-it-is-likeness.

Q: You’ve always demonstrated a playfulness in your work, whether it be through using the condition of zombiehood to explore father-son relationships, or videogames to discuss sight, or competitiveness in academia while dissecting Hitchcock films. Other Minds and Other Stories feels even more playful to me, and to possess even more humor than your previous work. One of my favorite stories is “Pecking Order”: it’s about an ambitious locavore couple who are facing a move and forced to euthanize their chicken flock. It is absolutely, mind-blowingly hilarious. Another incredibly funny story is “Introduction to the Reading of Hegel” - the title may suggest a rather dry subject matter, but it’s a comic portrait of an academic facing down crippling anxiety and writer’s block. Do you take the same approach to writing humor as you do with all your writing?

BS: Thanks for the kind words. I’m gratified you found these funny. They’re very different from each other, but maybe the comedy in them works the same. Both are staging a kind of collision between a character’s self-image—the story they tell about themselves—and some new situation that puts pressure on it. If the character can’t abandon their old stories, or adjust their behavior, they just keep bumping up against the walls of themselves, and we cringe or laugh at their trapped-ness. In ‘Pecking Order,’ the protagonist strives to be a good person (progressive, environmentally responsible, nonviolent, etc.), and he tries to maintain that self-image even while beheading a chicken in his backyard. But the chicken, reasonably, doesn’t want to die: as it fights back, its refusal to let him give it a ‘good’ death is what enrages him. The angrier he gets, the more violent, resentful, and sadistic he becomes, until he has difficulty thinking of himself as good at all. There’s a lot of slapstick violence in the story (malfunctioning hedge clippers, bitten fingers, etc.), but the comedy is also a slapstick of self-image. It’s funny to watch his idea of himself fall down. The chicken’s like the banana peel his self-image keeps slipping on.

Likewise for ‘Introduction to the Reading of Hegel’: the protagonist is a philosophy student who feels rigorously defended by self-hatred. He tries to anticipate everything that other people might hate about him—and to hate himself for it first—in order to preempt their hatred. So if he’s never read Spinoza, he imagines a hypothetical Spinoza scholar holding him in contempt for his ignorance, and that’s enough to make him make himself read Spinoza. When the story begins, it’s his last night to apply for an important fellowship, and he becomes convinced that his judge will be a Hegel scholar. He’s never read Hegel, and now there isn’t any time, and so he enters a doom spiral. Again, the comedy comes from the collision between his self-image and this situation. Does he cling to his old story about himself, and stay up all night hate-reading Hegel? Or does he adapt to the circumstances, and apply to the fellowship without, for once, self-hatred’s ‘help’? Writing it out like that, I guess it doesn’t sound all that funny, but I’ll let readers take your word for it that it is. I think I do approach comic stories like these in essentially the same way as I would a horror story, or a story of lyric description. Once I know what a character’s voice sounds like, I like to follow them into narratively charged situations, to see what happens to their sentences or their sense of self under pressure.

Q: Having now published a novel and two story collections, what excites you about the short story form?

BS: It probably is that exploration of a self under pressure. With that said, drafting is usually a form-finding process for me. It isn’t always clear to me whether something is a short story or a novel, until I finish it. Typically all I begin with is a voice, a character’s sentence style or rhythms of thought. I can find myself writing riffs and vignettes from their point of view, for dozens or sometimes hundreds of pages, without knowing what narrative container is going to take shape around them.

To take ‘Introduction to the Reading of Hegel’ as an example: this is a project I first started a decade ago. I was trying to write about the motivational properties of self-hatred. You hate yourself for not having read a certain book, and sometimes this hatred makes you read it. Writing about the weirdness of this, I arrived at the sentence: ‘that was the philosophy that had fueled his reading: not the love of wisdom, but the wisdom of hatred.’ I liked the character who would think this sentence. I knew that I wanted to construct a narrative that could contain his voice. But would it be a novel? A story? Who was this character anyway? What was happening in his life to make him think this thought, and what did the act of thinking it make him do or change? What book did he want to read, and why? For a long time I didn’t know. I would put the project aside and write other stories. A year would pass, and I would open the Word document, reread the sentence, and write new riffs and vignettes from within that voice.

Eventually I did find a narrative container for it, in this story. The character is a grad student, and he hates himself for having never read Hegel. The story takes the form of a Bernhardian block-paragraph, and it transpires over a single anxious night in a library. But there’s a sense in which these narrative details are all secondary to the original sentence. The story is just the container I was able to find for it, the vat I finally fashioned for this brain to think that sentence in.

If anything excites me about short stories, I suppose that’s it: that in their formal and stylistic variety, they can contain a wide variety of voices and modes of thought. This collection features many different kinds of characters (jealous lovers, writers, private detectives) in many different situations (investigating mysteries, killing chickens, hate-reading Hegel) in many different narrative forms (numbered fragments, ekphrastic analysis, block paragraphs). The structural compression of the short story allows you to dwell inside these minds during their most meaningful moments, in states of pressurized emotion or attention or intensity, when they’re thinking their most interesting and consequential sentences.

Q: Several of the stories take place in Rome, where you lived for a period after having received the Rome Prize for Literature. How did that experience shape your work?

BS: Rome is a beautiful city, and the American Academy was an incredible residency. It’s interdisciplinary, so there were painters there, and historians and archaeologists, architects and landscape architects, photographers, puppeteers, filmmakers, art conservators, composers, classicists. You’re having lunch and dinner with these brilliant people every day, going to their lectures, going on field trips together. I wanted to be as much of a sponge as I could that year, to soak up my cohort’s curiosities. The experience shaped my work in pretty basic ways: stories are set in Rome and at the Academy, and I wrote them while I was there. A couple were written as collaborations with the photographer Sze Tsung Nicolás Leong, a fellow fellow who became a friend: he invited the other fellows to write brief texts to accompany the photographs he was taking around town.

But my time at the Academy probably also shaped my interest in this question of ‘other minds’ more generally. It was fascinating to look at Imperial coins or vaulted ceilings or Etruscan jugs with people who had devoted their lives to them: to see that object through their eyes, and get that contact high off their consciousness. I try to dramatize that experience in the collection, where a lot of the stories just involve characters experiencing artworks alongside one another. They’ll watch a movie, or read a book, or look at an Etruscan jug, and wonder how the people around them are reacting to it: ‘What is it like for them to experience this artwork?’ Or: ‘How can I share my own experience? How can I convincingly convey what’s going on inside my mind, and get them to see what I see?’

I suspect that my time at the Academy sensitized me to these questions. This is why the Rome stories in the collection ended up being so ekphrastic, revolving around sarcophagi, statues, mosaics, pottery, landscape installations. They turn on the question of what it means to encounter ancient art—or any art—as this ancient encounter with otherness.

Q: One of the things that struck me, especially with the last story which is very short and massively impactful, is a consideration of “the classical project of literature,” especially juxtaposed with the deterioration of the artwork in Roman museums and portrayed in the book. Film also plays a role in much of your work. This is a loaded question, but how do you see literature fitting in within the broader cultural landscape, especially in the United States?

BS: The final story is one of the ones that I wrote for Nicolás. He took a photo in the House of Literature in Rome, of this cool Medusa mosaic in the hallway. The presence of a gorgoneion in a library interested me. What was the significance of this librarian who turns her readers to stone? Why, as the story’s narrator wonders, would you hire a gorgon to guard the archive?

I found myself thinking of an essay by the poet Aaron Kunin, ‘Shakespeare’s Preservation Fantasy.’ Kunin is interested in the immortality project of poetry, the desire to defeat death by preserving a mind in language. In this tradition, language is figured as an ultra-lithic material: sentences, unlike stone, don’t erode, so the poem gets pitted against the pyramid or the statue as a more durable monument. Kunin tracks this project from Horace (the poem as pyramid for the poet) through Shakespeare (the poem as pyramid for the poet’s beloved) to Milton (the poem as pyramid for the poet’s readers, who are statuefied in admiration of him: ‘Thou in our wonder and astonishment/Hast built thyself a livelong Monument…Then thou our fancy of itself bereaving/Dost make us Marble with too much conceiving’). I was also influenced by Michael Clune’s thinking about this tradition, in Writing Against Time.

So in the story, when the narrator refers to ‘the classical project of literature,’ that is what they mean. The narrator is considering how literature might fashion a ‘superior statue’ of a person, preserving a sculpture of their mind. This is how the narrator comes to understand Medusa’s function in the library: like a poem, she turns people to stone. And the story is itself a kind of sculpture of the narrator’s mind, during this one moment in time. It’s a statue of ekphrastic capture, recording all the thoughts the narrator is thinking while encountering this mosaic (or Nicolás’s photograph of it). In that sense, Medusa has turned the narrator to stone after all, whatever stone the story is.

I wonder whether this touches on your concern about literature’s broader role in the culture. I’m persuaded by the claims that get made for literature’s uniqueness as a medium of interiority, its ability to represent or reproduce consciousness. There’s an intimacy to the inness of a novel or poem that I don’t get access to in even other narrative art. While I enjoy films or videogames or whatever as much as the next person, I don’t feel that literature is threatened or obsolesced by them, because books seem unsurpassed as statues of thought. If I want to know ‘what it is like’ for Clarice Lispector, I’d still rather read The Passion According to G.H. than play a first-person roach-eating simulator (though I would love for someone to make a game of that novel). I assume anyone reading this interview feels the same way. I try not to be naïve about the material conditions of literature and its production (the publishing industry, the academy, etc.). But I remain optimistic about literature as an enterprise: as long as people are thinking interesting thoughts, and are curious about each other’s thoughts, it seems like writers will keep writing them down and readers will keep reading them. Even in the United States.

Booksellers, librarians, or critics interested in receiving an advance copy of Other Minds and Other Stories can request a copy.

Pre-order Other Minds and Other Stories.

(Author photograph by Alice Zoo.)

On June 6, 2023, we're thrilled to be publishing journalist Kathryn Bromwich's debut novel, At the Edge of the Woods, in a super classy paper-over-board hardcover edition that we've come to adore. At the Edge of the Woods is a rich, gorgeously descriptive and remarkably assured story enthralled with nature, that I've been describing as if Richard Powers wrote a Shirley Jackson story.

Sarah Rose Etter, author of The Book of X, calls it "A rich and bewitching novel. Kathryn Bromwich has spun up a delicate world that interrogates the dark side of love, the wild power of nature, and the strength it takes to break free." Maryse Meijer, author of The Seventh Mansion, calls it "a stunning experience not to be missed."

The story takes place in the first half of the twentieth century, and follows a woman named Laura who lives in a remote cabin in the Italian Alps. She’s left her husband, and appears to be in hiding. Laura spends her days alone, rekindling her sense of self by exploring nature and the countryside around her. The cabin is on the fringes of a quaint, conservative, religious town, and when Laura ventures into the village for supplies, she’s met with curious stares and wariness. Laura begins seeing a bartender, who informs her of the villagers’ suspicions.

One day, someone from Laura’s past appears, alerting her to all that has transpired since her disappearance. Meanwhile, Laura’s behavior becomes more erratic, which causes the villager’s suspicions and mistrust of her to mount, and accusations of her being a “strega,” a witch.

Kathryn Bromwich is a writer and commissioning editor on The Observer newspaper in London. She writes about all aspects of culture, including music, film, TV, books, art and more, and has contributed to publications including Little White Lies, Dazed, Vice, Time Out and The Independent. She has lived in Italy, Austria and the UK and is currently based in east London.

Following is an interview with Kathryn Bromwich about At the Edge of the Woods.

Question: The profound respect for nature in the book is palpable. Secluded in the Italian Alps, Laura goes on rigorous hikes, immersing herself in the natural world, and in so doing grows to better understand herself and the world around her. How did concerns for the environment come to be interwoven with the storyline?

Kathryn Bromwich: I didn’t set out to write a book about the climate emergency. I mainly wanted to write about mountains: I have been suffering from long Covid, and found myself drawn again and again to these landscapes, probably because of their grandeur and stillness. For a long time I felt trapped, both inside the flat and my body, and the mountains offered a powerful sense of freedom and escape. Through writing I could relive my experiences hiking in Italy, France, Austria, Scotland, California, Peru – something I loved doing before falling ill and which I am still not sure whether I’ll ever be able to do again. But while writing, there was no way of escaping the reality of what is happening all over the world: catastrophic floods, deadly wildfires. Saint-Martin-Vésubie, a beautiful village in the French Alps where I went hiking a few years ago, was recently ravaged by a violent storm: several people died, houses were destroyed, landslides wiped away huge swathes of the mountain. Extreme weather is now the norm. Reading the news every day was like that moment at the end of nature documentaries where they tell you that all the incredible things you’ve just seen are dying, and we are to blame. That sense of loss definitely informed the writing: I don’t think anyone could write about nature these days without being acutely aware of the dangers it faces. So while I wouldn’t say the climate crisis is the novel’s primary subject, it is a shadowy presence lurking in the background, biding its time.

Q: As the months pass with Laura living alone in the cabin, and as she becomes increasingly alienated from the traditional mindset of the villagers, she begins to drift further into nature and further into herself, experiencing mystical visions. How do you see the surreal imagery meshing with the fabric of the book?

KB: It’s an integral part of the book, but I am wary of explaining my reasoning around it too much – I think it’s up to readers to decide what it means for them, as it will be slightly different for everyone. What I will say is that I was meditating a lot when I started writing, and I was reading widely about mysticism, neuroscience and trauma – the Upanishads, Margery Kempe, William Blake, Emanuel Swedenborg, Bessel van der Kolk, Lisa Feldman Barrett. I became fascinated by experiences that could be interpreted as moments of enlightenment, or madness, or somewhere in between. Most definitions of mystical visions share certain specific characteristics: a sense that the person is experiencing something of the utmost importance, more real than the real yet ineffable, an experiential understanding of the deep interconnectedness of all things; often, these experiences can offer a powerful way of working through painful memories. This is a state that can be achieved by letting go of the ego, either through psychedelics or certain forms of meditation or through more mysterious means. I was very attracted to this idea that there could be another layer of reality enmeshed with ours, and the ways it could be accessed. The best description I’ve found of this was in a recent interview with Nick Cave in which he talked about the “imaginal realm”, a term from priest and religious writer Cynthia Bourgeault: Cave calls it “a kind of liminal state of awareness, before dreaming, before imagining, that is connected to the spirit itself. It is an ‘impossible realm’ where glimpses of the preternatural essence of things find their voice.” That state of liminality is at the core of many aspects of the novel, so I wanted to explore what such a realm might look like.

Q: The book addresses expectations of what might be considered traditional femininity, through the expectations the villagers and her husband impose on Laura. Even though the story is set in an earlier time period, do you feel as though these questions are still topical?

KB: Absolutely – we are seeing now, especially in the UK, how trans women are being increasingly excluded from women-only spaces, how their very existence is being questioned. Anyone who is considered to be outside of “the norm” is feared and rejected. This anti-trans (or, as they like to call it, “gender critical”) discourse is narrowing the idea of what a woman is to a purely biological perspective, which not only excludes anyone who is trans or non-binary, but also anyone with medical conditions that fall outside of their parameters. Maybe it’s just me, but defining women based on their reproductive organs doesn’t feel like progress. There is also a strange insistence from certain quarters that unless you are a mother you don’t truly understand feminism, which is a spectacularly backwards step. As we learn more about intersectionality and different lived experiences, feminism should be getting more expansive and inclusive, not less. But even though more and more women are deciding not to have children, the world is very much geared towards nuclear families. When you hit your early-to-mid-30s, a shift starts to happen: people move out of the city, and suddenly nights out are replaced by hen dos and baby showers. Everything becomes a lot more gendered, which can be quite disconcerting if you have an uneasy relationship with femininity. So I’m writing for any women and non-binary people who feel excluded from the term, or who are unconvinced by the traditional gender roles we’ve been raised to believe in.

Q: There are just so many elements of At the Edge of the Woods that I admire, from its discussions of class, infertility, its tonal meandering through the natural world, and also the subtle, ratcheting tension of the story. There were times as the sense of menace and dread was building, where it felt to me like a creepy fable, or a Shirley Jackson tale washed in acid. I know in discussing it with you that so much of the book came from the experience of long Covid, and the effect it had on your mind and body, but how concerned were you with creating a sense of mounting unease and tension as you crafted the story?

KB: The past two and a half years have been like being trapped inside a horror story, both on an international scale and a personal one – apocalyptic dystopia and Cronenbergian body horror. Not only have we lived through a global pandemic, but the virus has attacked every part of my body: my lungs, my heart, my muscles, my nervous system. I am slowly improving but I can only work in short bursts, I can’t exercise, I need constant rest, I have terrible insomnia. It’s still unclear whether I will ever fully recover, and the psychological effect of that has been devastating. A lot of people felt a profound sense of isolation during the pandemic, but this feeling was magnified by illness, and now that things have opened up again it has only intensified. At times it has felt like inhabiting a ghost story: life goes on for other people but I feel frozen in time, existing alongside the rest of society but unable to join. Writing was a way for me to process these feelings, though I should clarify that this is very much not an autobiographical novel – I live in central London rather than a cabin in the woods, and I have not quite lost grip on reality to the extent the protagonist has (I hope). But I did want to capture some of that feeling of dread and mounting frenzy, then dial it further and further up to see where it would go.

Q: Laura comes to be flagged by the villagers as a witch, and At the Edge of the Woods takes place in the late-19th or first half of the twentieth century. You are British and Italian, and your Italian great-grandmother was apparently considered a “witch” — was there any seed of inspiration there for the story?

KB: That was in the back of my mind when I was writing, but the character is not based on my great-grandmother in any way, except perhaps that she comes from the Adriatic coast and descends from fishermen. But she was never persecuted or cast out from society or anything of the sort – it is my understanding that she was a “good witch” who “healed” people from various ailments, and they would come from all over Italy to be cured by her. I don’t know how effective her treatments would have been, but I’m intrigued by the fact that this was something she felt called to, and that people believed in it. I think the reason witches still hold such a powerful hold over people’s imaginations is that it was a catch-all term used to describe women who were in any way different, or whose behaviour went against the grain. Most women alive today would probably have been considered witches at some point in the past.

Q: Do you feel as though your non-fiction writing on culture influenced or shaped your fiction writing in this novel? Having interviewed so many incredible and brilliant artists yourself, was there anything anyone said to you over the years that influenced your approach to this book or to this story?

KB: A lot of the elements that make good non-fiction writing still hold for fiction: clarity, structure, precision. You have to (hopefully) be entertaining. But there are also many aspects of fiction that are in some way the opposite of journalism – making things up, stepping away from the factual, including your own thoughts and feelings. So it was a bit of a struggle to let those things go. I started writing a dystopian sci-fi novel a few years ago which was very “issues”-based and probably quite didactic. With this project I wanted to do something completely different, much more personal – turning inwards rather than outwards. But as I was writing I noticed that themes such as feminism and the climate crisis kept creeping in: it’s impossible to escape the real world even if you’re writing fiction.

One of the best things about my job is that I get to speak to so many interesting people about their art, so there are too many to choose from. I enjoyed talking to Michael Pollan a few years ago about Richard Powers’ The Overstory and the ways trees communicate, which must have sparked something in my mind. Pulp singer Jarvis Cocker was fascinating about illusions versus reality, and I liked what Perfume Genius said about PJ Harvey talking to the devil “and magnifying her darkness” in her art. I was also very struck by something Samanta Schweblin said, about how a novel happens half on the page and half in the reader’s mind, but how what happens there has been well calculated by the writer. So that was something to aim for.

Pre-order At the Edge of the Woods.

If you are a bookseller, librarian, or critic interested in receiving an advance review copy of At the Edge of the Woods, request a copy here.

Rodrigo Restrepo Montoya’s cool voice and poetic prose immediately drew me in to The Holy Days of Gregorio Pasos. I found the story of his young protagonist—a child of Colombian immigrants now living in the U.S., finding his way in the world on the eve of the 2016 presidential election—to be both illuminating and remarkably touching.

Entrancing and sentimental, told with wit and sharp insight, The Holy Days of Gregorio Pasos examines the joys and traumas of the Latinx American experience through the lens of a young man awakening to the nuances of identity, love, colonization, and home. We are thrilled to be publishing this compassionate, poetic, and thoughtful debut novel on July 11, 2023.

Here is more about what the story is about:

As Gregorio recovers from a soccer injury, he relives a decisive period of his life when he is eighteen and adrift. His parents are divorcing, his sister is estranged, and his poor goalkeeping has just cost his soccer team their most important game of the season. As a graduation present, Gregorio’s defiant uncle Nico takes him to Colombia, where he is introduced to old friends, family memories, and a culture ailing after years of conflict and colonization. When they return, Gregorio follows in his uncle’s footsteps and pursues employment at an art museum in Washington, D.C., where he moves into the basement of a townhouse owned by Magdalena, a Basque exile he befriends. As the year wends on and anti-immigrant rhetoric reaches an apex, Gregorio notes the disparities in his community while struggling to define his own identity and direction. Gregorio joins his friend Raul’s soccer team, resuming his role as goalkeeper, seeking purpose and redemption.

What follows is an interview with Rodrigo Restrepo Montoya about The Holy Days of Gregorio Pasos, humor, immigration, art-making during periods of uncertainty, and goalkeeping.

Question: What struck me when I first encountered your manuscript was the voice of the protagonist, Gregorio Pasos. He’s very cool and calm, with a dry sense of humor; he’s incredibly endearing and sensitive, but also most certainly not reactionary. How did you arrive at Gregorio’s voice?

Rodrigo Restrepo Montoya: Early on in the life of the project, a family member of mine described Gregorio’s voice as elemental. This made me very happy and stuck with me throughout the many drafts that came after. In a way, this became the ethic of the novel. Like many writers, I wanted to write something that got at the core of what it means to be human. By extension, I also wanted to get at the core of what it means to be Colombian and American, among other things. What Gregorio seeks is no different than what I sought to execute with the book. I figured that the use of natural and readable language was the best way to go about the project. It was important to me, also, to create a narrator that readers wouldn’t mind spending time with.

It’s funny you mention humor. Of all your descriptions of Gregorio’s voice, humor came out gradually. The earliest versions of the novel were quite sentimental. This was, I supposed, the most fitting way to communicate Gregorio’s growing personal, cultural, and political awareness. Over time, Gregorio became less of a character and more of a person. A friend. With every draft he got funnier. Facundo Cabral, an old Argentinian folk singer, combined these elements extremely well. His songs are unbelievably plain and lucid, and are often equal parts sentimental and humorous. These two elements work together to keep the ideas going. In other words, he’s funny but he’s not joking.

Q: The story follows Gregorio during a formative year in his life, when he’s 18-19 years old, as he’s realizing some crucial things about his own identity. This happens against the backdrop of the U.S. in 2016, when people are chanting to “build the wall” and the country is about to elect a xenophobic president. Gregorio is awakening to his own identity, but also to the true nature of the U.S. during this time. How did this dual awakening shape the arc of the story, and were you always intent on anchoring the story during this time period?

RRM: I began working on The Holy Days of Gregorio Pasos in 2014. The political themes of the project were the same then as they are now: colonialism, emigration, immigration, deportation, fascism, exile, etc. Then the election happened and it felt irresponsible not to set the book in 2016, a time period, among so many others, that perfectly embodied America’s synonymity with violence. 2016 marked a shameless celebration of American absolutism. In regards to writing this book, it became important not to ignore this escalation – what was, at the time of writing, the present.

Q: You also have Gregorio visit his parents’ homeland of Colombia with his sick uncle Nico, who reflects on his own coming-of-age in a country engaged in prolonged war. The trip exposes Gregorio to issues of Indigenous rights and colonization. It’s an interesting juxtaposition, especially considering the politics in the U.S. in 2016 and the attempted coup in 2021. Did you always intend for the book to have such an international outlook?

RRM: Yeah, I think so. The United States and Colombia are the two countries and cultures I know best. It’s always felt natural to write about them. My parents were born and raised in Colombia. Almost all of my extended family lives there. I was born and raised in the United States but have spent a lot of time in Colombia as well. A few other countries play a role in the book. Magdalena speaks at length about being a Basque exile, about Franco and fascism. Mexico also plays a role. The fundamental triangle at work, I suppose, is formed by Colombia and its two empires – Spain and the United States.

I wanted The Holy Days of Gregorio Pasos to take a somewhat sweeping look at the past and present of colonialism and the ways it permeates every aspect of daily westernized life. While American history is a distubringly accurate representation of colonial history, the world is simply much bigger than the United States. Entire parts of the planet are invisible to most Americans, Latin America and its people included. It’s particularly upsetting when you think about the United States’ exploitation of Latin America’s labor and natural resources. And that’s putting it mildly. John Bolton, Trump’s Former National Security Advisor, bragged on CNN about having planned several coups in foreign countries. The news came and went.

Q: How do you see cultural preservation pertaining to the book?

RRM: The experience of working on this project made me really interrogate the value of a book, especially during a time period when the future has seemed pretty bleak. I thought a lot about what art can and can’t do. Many forms are present in this book – painting, sculpture, photography, film, sport, song. They range from devotional to celebratory to political. As does The Holy Days of Gregorio Pasos.

In the end, I felt that one of the book’s fundamental responsibilities was to try to contribute something to our collective memory. I don’t expect that one book, mine included, will make any kind of real difference. But maybe it helps someone, some way. History matters. It’s with us all the time. I wanted to write a book that approaches history on a human scale. People are sacred, therefore art is sacred too.

Q: Despite Gregorio being a young man, two of his most impressionable relationships are with older people: his sick uncle Nico, and Magdalena, from whom he finds inexpensive lodging in D.C. in exchange for the upkeep of her house. How do Nico and Magdalena imprint themselves on Gregorio?

RRM: Both Nico and Magdalena emphasize an attention to history and its relationship to the present. Both are products of their respective histories. Nico is a Colombian emigrant. Magdalena is a Basque exile. Nico is generally focused on colonialism; Magdalena on fascism. But at the end of the day their relationships are very human. Gregorio comes to be something like a son to Nico, who has no children of his own. He and Magdalena, a widow, grow close beyond their living arrangement.

Overall, I think I’ve always been interested in how people see and talk about themselves, the lengths they do or don’t go to make themselves known. The stories people tell about themselves can be quite revealing – they tend to be even more illuminating than the facts of a person’s life. Gregorio listens to Magdalena and Nico. They do the same for him. They take care of each other. The same is true of most characters in the book. The Holy Days of Gregorio Pasos is composed of people who rely on one another in tender, necessary ways.

Q: Gary Shteyngart blurbed a book for us, called How to Get Into the Twin Palms by Karolina Waclawiak, and referred to the children of immigrants as a 1.5 generation, in how they are at a crossroads between their parents’ culture, and assimilating within American culture. Do you feel this applies or not to Gregorio’s place in the world of the book?

RRM: I think the 1.5 designation is pretty accurate. Gregorio is certainly between two cultures. There are times where he feels more a part of one or the other. Sometimes he’s a part of both, sometimes he’s neither. It’s an interesting position, but it’s a common one. A lot of people experience some form of displacement. The characters in this book represent a range of these displacements, ranging from addiction to exile to deportation. Gregorio finds himself very much at the in-between. He occupies a vantage point where every situation he encounters is at once familiar and foreign. He is amid two distinct ways of understanding and interacting with the world. His life more or less requires him to exist in a constant state of observation.

Q: Gregorio plays goalie on his high school soccer team, and then in a recreation league in D.C. How do you see that position fits Gregorio’s personality?

RRM: The roles we play, however insignificant they might seem, end up adding up to how we operate in the world. A goalkeeper is someone who is responsible, above all else, for not making any mistakes. They do not impose themselves on the game they play. They abide by the circumstances and do their best to prevent the worst possible outcomes. Generally speaking, it’s a thankless job. Several schoolyard versions of soccer involve playing goalie as a sort of punishment. Professional goalkeepers often get paid less than their teammates, even if they are better at what they do.

Gregorio is a goalkeeper in just about every aspect of his life. This is true of his relationships and of his work. He might be the protagonist of The Holy Days of Gregorio Pasos, but he is secondary to the proverbial plot.

Pre-order your copy of The Holy Days of Gregorio Pasos.

| Read more →

In March 2023, we are publishing the debut work of non-fiction by acclaimed fiction writer, Robert Lopez, a masterful consideration of memory and cultural preservation called Dispatches From Puerto Nowhere: An American Story of Assimilation and Erasure. The book dives deep into Lopez's Puerto Rican heritage, going back to his grandfather, Sixto, who immigrated to Brooklyn in the 1920s. There isn't much known about Sixto, or what inspired him to move to New York in the first place, and even less passed down in terms of family stories, language, or the Puerto Rican culture to the point where Robert feels — only two generations removed — as though he might be Latin In Name Only.

Dispatches From Puerto Nowhere braids Sixto's journey from Mayaguez to Red Hook, Brooklyn, where he works as a longshoreman and starts a family, with Robert's own upbringing in the predominantly white suburbs of Long Island, grappling with racial slurs and the thought of how much his family's assimilation was intentional, as well as how much he benefited from that assimilation. Having lived most of his adult life in Brooklyn, Lopez reflects on the diversity and rich heritage of his tennis community.

Dispatches From Puerto Nowhere is marvelous, thoughtful, and compassionate, and stands as a testament to Lopez's tremendous dexterity and prodigious talent as a writer.

Justin Torres, author of We the Animals, calls the book:

"A masterpiece clear and honest and alive to the world and its contradictions. Dispatches From Puerto Nowhere will hit you where you live."

Nick Flynn, author of This Is the Night Our House Will Catch Fire, The Ticking is the Bomb, and Another Bullshit Night in Suck City, says:

"Dispatches From Puerto Nowhere is a deceptively subversive book, full of insights and humor and a level of honest examination (both of racism and of the author himself) that is rare. Lopez writes in distilled bursts, each labelled 'Dispatch from…' (A Better Moment; Something Irretrievable; It’s Now or Never, etc), as if he wasn’t standing right beside us, murmuring these complicated truths in our ears, but beaming them in from some distant, forgotten past. He carries the weight of this past, yet it does not crush him. Or—thankfully, beautifully—us."

Ander Monson, author of The Gnome Stories and I Will Take the Answer, says: "Robert Lopez’s Dispatches From Puerto Nowhere is somewhere between a speculative memoir, a mostly unresolved detective story, and a meditation on learning to play tennis. That it’s none and all of these things—and more—is its particular genius."

Following is an interview with Robert Lopez about Dispatches From Puerto Nowhere: An American Story of Assimilation and Erasure.

Question: At this point you’ve published four novels and two collections of stories. What made you realize that you wanted to branch out into non-fiction, and why with this story in particular?

Robert Lopez: I can’t quite remember the genesis of this particular project. The first essay I wrote started with the line “The first time someone called me a spic was during recess or after school in the playground or in the park across the street from my house.” I think I wanted to talk about the disconnect I feel to my heritage and this was the sentence that presented itself as a way in. Most of what I’ve done with prose seems to concern confusion and uncertainty. I realized I didn’t know anything about my grandfather and starting from that kind of ignorance is right in my wheelhouse.

Q: While your various family members have Italian, Spanish, and Cuban ancestry, why do you think it is that the Puerto Rican line, and your grandfather Sixto Lopez, is the one that you seem to feel the most drawn to and chose to focus on with this book?

RL: I always thought of myself as Puerto Rican first when it comes to the entirety of my ethnic makeup. It’s my name. And Sixto made for an interesting character for all the reasons that are illustrated in the book and what I mentioned in the first answer. I realized I didn’t know anything about him and started to wonder why that was the case. That he was a musician, superstitious, and a prototypical Latino from that mostly/hopefully bygone era when it comes to the male/female dynamic, made for a meaty skeleton to start with, at least.