China and the Imprisoned Hong Kong Booksellers

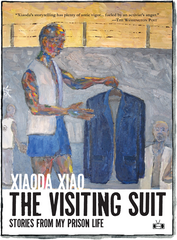

There seems to be a persistent trickle of news regarding blatant and shocking human rights violations that persist to this day in China. I've seen the documentary about Ai Weiwei, Never Sorry, and was directly made aware of the government's continuing censorship when we published Xiaoda Xiao's books, the novel The Cave Man and his memoir, The Visiting Suit: Stories From My Prison Life.

Xiao was inspired to write about his experience in one of Mao's labor prisons, where he spent seven years in a stone quarry as punishment for accidentally tearing a poster of Mao, after being freed and encountering a popular version of prison literature that romanticized the experience. It was his intention to portray an accurate representation of what life was like in a Chinese labor prison.

At the time we were about to publish The Visiting Suit, I had heard that the government still censored publishers and writers, which surprised me. As a publisher, we receive queries from printers constantly, from those based domestically and abroad. I decided to see whether a Chinese printer would print The Visiting Suit for us. Not surprisingly, they refused, and I can't blame them, because doing so would mean that they would be punished. Printers in China employ censors to review work that they're about to print to ensure it won't antagonize the government party.

At the time we were about to publish The Visiting Suit, I had heard that the government still censored publishers and writers, which surprised me. As a publisher, we receive queries from printers constantly, from those based domestically and abroad. I decided to see whether a Chinese printer would print The Visiting Suit for us. Not surprisingly, they refused, and I can't blame them, because doing so would mean that they would be punished. Printers in China employ censors to review work that they're about to print to ensure it won't antagonize the government party.

Last year, Chinese authorities quietly apprehended five booksellers and publishers, snatching them from Hong Kong, China, and Thailand, and then detaining and torturing them. They were arrested for their connection to a series of books banned in China, that pertain to "gossipy accounts of the private lives of senior Communist Party figures."

Lam Wing-kee, who was tortured by his Chinese captors fishing for information on Chinese citizens who had purchased copies of the gossip books from Lam's Hong Kong bookshop, managed to escape custody. He had been returned to Hong Kong from China in order to retrieve a list of customers, the Chinese authorities expecting him to return, which he did not.

Lam said in a statement:

"I also want to tell the whole world. This isn’t about me, this isn’t about a bookstore. This is about everyone. This is the bottom line of the Hong Kong people. This is Hong Kongers’ bottom line—Hong Kongers will not bow down before brute force.”

There are still Hong Kong booksellers imprisoned in China, and the daughter of one, Gui Minhai, testified to Congress in May about her father's detention. The Senate's Congressional-Executive Commission on China released a statement calling the detentions "illegal," adding they will "have serious economic and security implications."

After we published Xiao's books, he returned to China for the first time in many years. He had a small reunion with friends he had from the labor prison. Once he returned to the U.S., I asked him how it went. It was a success, he thought, because neither he or his friends had been followed or detained.

Comments