An Interview with Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib

In an age of confusion, fear, and loss, Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib's is a voice that matters. Whether he's attending a Bruce Springsteen concert the day after visiting Michael Brown's grave, or discussing public displays of affection at a Carly Rae Jepsen show, he writes with a poignancy and magnetism that resonates profoundly.

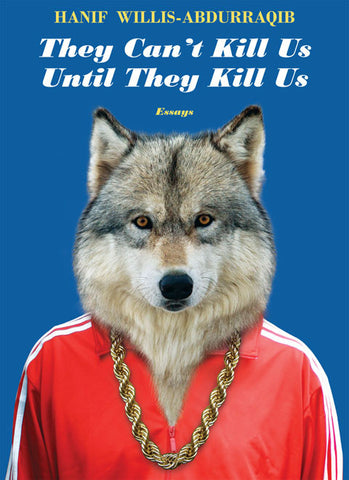

We are beyond thrilled to be publishing Hanif's first collection of essays, They Can't Kill Us Until They Kill Us, this November.

In essays that have been published by the New York Times, MTV, and Pitchfork, among others—along with original, previously unreleased essays—Hanif uses music and culture as a lens through which to view our world, so that we might better understand ourselves, and in so doing proves himself a bellwether for our times.

Following is an interview with Hanif about his forthcoming collection, his eclectic taste in music, hometown of Columbus, and our politically charged times.

Q: You have quite the taste in music, from Chance the Rapper to Fleetwood Mac. How did you get into listening to such a broad spectrum of music?

Hanif: I think I owe this to the household I grew up in. My parents had deep record collections, with a lot of range. My father and brother would play instruments in the house. I’m the youngest of four, so I got to absorb all of the music that my older siblings were into, and I got to do it at the dawn of the 90s, when so much was happening. I grew up not just centered on hip hop, but also jazz, funk, soul, grunge, punk. Especially when sampling started happening heavier in rap songs. It awoke a kind of hunger in me, to find the roots of everything I was falling in love with.

Q: I think that reading books by authors from other parts of the world or even the country does create empathy. Do you believe the same might be true for music?

Hanif: I think it depends on who is making the music, yeah? I mean, decades of rap music hasn’t really made America, at large, approach marginalized communities with more empathy. In the book, there is a piece about how listening to The Wonder Years (band) play songs about the strains of suburbia opened up a window for me as a teenager. It gave me a way to connect with kids who I played soccer with, kids who lived on suburban streets just a few blocks away from my decidedly non-suburban streets. It re-shaped my idea of what their lives were like, and that not everything was perfect. So, I think I’m saying that it all depends on who is making the music, who is listening to the music, and what they’re listening for.

Q: Do you approach poetry differently than you would music criticism or an essay, and how do the different mediums inform one another?

Hanif: I think I became a better writer, in both realms, when I allowed the work to begin informing all of the other work. Poetry develops slower for me internally, sure. But by the time I approach the page, I’m comfortable just becoming a writer and living with whatever comes out. There are essays in this book that could easily be poems with some small restructuring of language and space. I’m interested in tricking people into reading poems in that way. So many people are in love with poetic elements of writing, but insist that they don’t love poetry. So how can I challenge that? It’s maybe the only question I’m returning to consistently these days.

Q: Everything feels especially political in this moment, whether it’s the concert you go to, whether you drink Yuengling or wear New Balances, or what non-profit you publicly donate to on social media. Rather than asking what you believe the role of the artist is in this day and age, I’m going to ask whether anything good can come from this moment, or are we just going to get a bunch of shitty U2 songs?

Hanif: I think it’ll be the latter. I’m not sold on this political moment, with all of its oppressive machinery, creating a glorious spring of artistic awakening. So many artists will be directly in the teeth of this. Artists of color, women, queer artists. The people who have been creating into this moment before it was a moment. And I don’t know if I think there’s much benefit that this administration will have on their work.

Q: Your writing does an incredible job of tying together broad subjects—such as attending a Bruce Springsteen concert or anointing Chance the Rapper the artist of the year at MTV—with very personal stories or issues (such as visiting Michael Brown’s grave, or growing up Muslim in America) and does so with a narrative ascension that is incredibly compelling. I’m not sure there’s a question here, other than how do you balance broad topics with more local, personal ones?

Hanif: I come from the idea that music, pop culture, our relationships to these things can hold weight. If we are close to these moments, and have some kind of personal tie-in to the moment, it’s vital to share that. It’s about ways of seeing, I think. The critic or commentator, as I live in those definitions, doesn’t have to convince a reader of anything other than why they love what they love. I can’t convince people that Chance The Rapper is good. I can, however, connect them to the things about Chance that move me, or have an impact on my small corner of the world. I can, through that, try to convince them that this artist might have an impact on their small corner of the world. Building as many bridges as possible through personal moments, and hoping that one might be sturdy enough for people to cross.

Q: Can you talk about what your hometown means to you?

Hanif: In short, everything. I was born and raised in Columbus. I can identify home in a way that not everyone can. There are people I love who have traumatic relationships with their hometowns, home countries. There are people I love who moved so much when they were young that they don’t feel much of anything upon returning to where they currently have roots. And so I consider it a privilege to have a place that I love and am proud to be from. It’s a gift, and I really think it’s important to honor that. Even as I reconsider the flimsiness of borders, I am still so proud to be from Columbus. I’m proud to talk about it in my work and in my life. I’m proud to give it space to exist in places that might not otherwise allow it to.

Q: Powell’s Bookstore created a reading list for Trump. Would you be up for making a playlist (however short) for Trump?

Hanif: Sleater-Kinney — “Step Aside”

That’s it.

You can pre-order a copy of They Can't Kill Us Until They Kill Us now for 25% off on our website.

If you are a bookseller, librarian, or critic, interested in receiving an ARC of They Can't Kill Us Until They Kill Us, you can request a copy.

Comments